Postmodern Architecture: The Ultimate Fusion of Styles

Nov, 16 2025

Nov, 16 2025

Look around any city today and you’ll see buildings that don’t play by the rules. A skyscraper with a pediment like a Greek temple, a bank shaped like a giant chandelier, a library with a roof that looks like a crumpled paper bag. These aren’t mistakes. They’re deliberate. They’re postmodern architecture.

What Postmodern Architecture Really Is

Postmodern architecture didn’t just add a new style-it broke the rules of what architecture was supposed to be. After decades of cold, glass-and-steel boxes labeled as "modern," architects got tired of being told form must follow function-and nothing else. So they started mixing things up.

Where modernism stripped away decoration, postmodernism piled it on. Where modernism avoided history, postmodernism quoted it. Where modernism was serious, postmodernism was playful. It didn’t want to be pure. It wanted to be interesting.

Think of it like a remix album. Postmodern architects took elements from Gothic spires, Roman columns, Art Deco zigzags, and even Victorian gingerbread trim, then slapped them together in ways that made people laugh, gasp, or scratch their heads. It wasn’t about copying old styles. It was about reusing them like LEGO bricks to say something new.

The Birth of a Rebellion

The movement started in the late 1960s and exploded in the 1980s. Architects like Robert Venturi, Michael Graves, and Philip Johnson were tired of the blandness of International Style buildings. Venturi’s book Learning from Las Vegas was the manifesto. He argued that ordinary buildings-like roadside billboards and neon-lit diners-had more character than sterile corporate towers.

Johnson’s AT&T Building in New York (now 550 Madison) became the poster child. In 1984, he topped a 37-story office tower with a broken pediment-a classical architectural detail that hadn’t been used on a skyscraper in nearly a century. Critics called it a “Chippendale top.” The public loved it. Suddenly, buildings could be funny, ironic, even cheeky.

This wasn’t just about looks. It was a rejection of the idea that one style should rule the world. Postmodernism said: Why not mix? Why not celebrate diversity? Why not let a building tell a story instead of just serving a function?

Key Features You Can Spot

If you’re walking down a street and see a building that looks like it’s wearing a costume, you’re probably looking at postmodern architecture. Here’s what to look for:

- Historical references-columns, arches, domes, but twisted or exaggerated. A Corinthian capital might be made of stainless steel. A Roman arch might be cut in half.

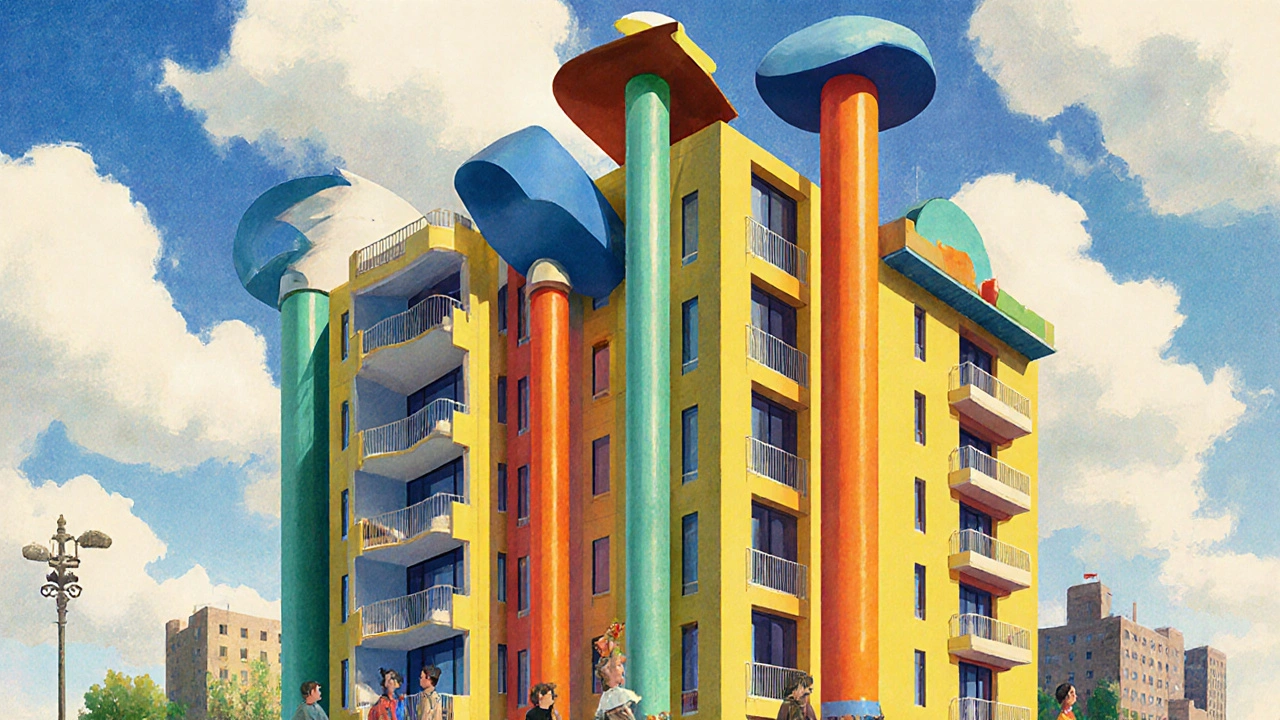

- Bright colors-not just beige and gray. Think coral, teal, mustard yellow. Michael Graves’ Portland Building is a classic example: a government office painted like a giant toy.

- Asymmetry-no perfect symmetry here. One side might have a giant column, the other a floating balcony.

- Playful shapes-buildings shaped like keys, shoes, or giant letters. The Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in London looks like a classical temple, but the roofline is broken like a child’s drawing.

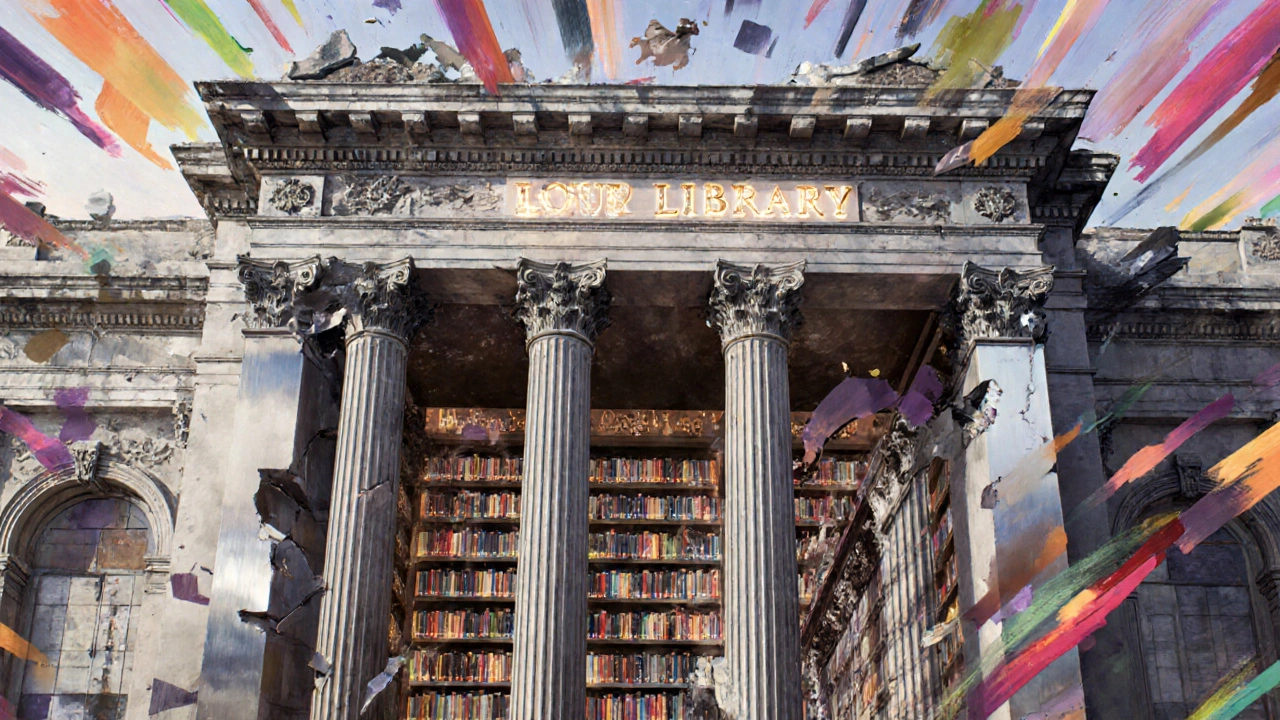

- Irony and humor-a building that pretends to be something it’s not. A parking garage designed to look like a medieval castle. A library with a facade that mimics a bookshelf.

These aren’t random choices. They’re intentional contradictions. A postmodern building might use classical proportions but make them too big, too bright, or too silly. It’s architecture that winks at you.

Real-World Examples That Define the Movement

Some buildings are so iconic, they became symbols of the whole movement.

The Portland Building (1982) by Michael Graves: This municipal office tower in Oregon was one of the first major postmodern public buildings. Its oversized columns, bright colors, and sculptural forms broke every rule of 1970s government architecture. It was mocked at first-but now it’s a landmark.

Vanna Venturi House (1964) by Robert Venturi: Often called the first postmodern house. It looks like a traditional American home-but the gable is too small, the chimney is fake, and the front door is off-center. It’s a home that plays with expectations.

The AT&T Building (1984) by Philip Johnson: As mentioned, its broken pediment sparked national debate. Today, it’s seen as a turning point-proof that skyscrapers didn’t have to be soulless.

The Piazza d’Italia (1978) by Charles Moore: A public plaza in New Orleans that looks like a Roman forum made of neon, stainless steel, and colored tile. It’s a celebration of Italian-American culture, built with kitsch and pride. It was almost demolished-but saved by public outcry.

These buildings didn’t just change skylines. They changed how people thought about design. Architecture didn’t have to be serious. It could be personal. Cultural. Emotional.

Why It Still Matters Today

Postmodernism isn’t just history. It’s alive in the way we design now.

Today’s architects still borrow from it. Look at Apple’s new retail stores: glass boxes, yes-but they’re framed with massive stone columns. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao? It’s not postmodern, but its curved, sculptural form owes something to the movement’s embrace of expression over function.

Even in housing, you see it. Boutique hotels that mix rustic wood with industrial steel. Apartments with exposed brick and neon signs. These aren’t accidents. They’re echoes of postmodernism’s core idea: that meaning comes from mixing.

And in a world obsessed with uniformity-cookie-cutter apartments, identical office towers-postmodernism reminds us that places should reflect people. That culture, history, and personality belong in the built environment.

The Criticism and the Comeback

Of course, postmodernism wasn’t without its critics. Some called it superficial-just decoration without depth. Others said it was elitist, mocking the poor with ironic references they didn’t understand. And yes, some buildings were just weird for weirdness’ sake.

But here’s the thing: the backlash led to something better. The next generation of architects didn’t throw postmodernism out-they absorbed it. Today’s best buildings don’t just mix styles-they layer them with meaning. A school might use local materials and traditional patterns to honor community history. A transit hub might borrow from regional crafts to create a sense of place.

Postmodernism taught us that architecture doesn’t have to be pure to be powerful. It can be messy. It can be contradictory. It can be joyful.

How to Spot It in Your City

You don’t need to travel to New York or Portland to find postmodern architecture. Look closer.

- Check out local banks or libraries built between 1975 and 1995. Many used classical details in unexpected ways.

- Look for buildings with mismatched materials-brick next to glass, stone next to plastic.

- Notice if a building has a detail that seems out of place: a tiny roof over a door, a giant arch that doesn’t lead anywhere.

- Ask yourself: Does this building feel like it’s trying to tell a story? If yes, it’s probably postmodern.

Even in Melbourne, you’ll find traces. The old RMIT Building 8, with its red brick and playful towers, nods to postmodernism. So does the former Carlton & United Breweries building-its gabled roof and ornamental brickwork are pure 1980s flair.

You don’t need to love it. But you should recognize it. Because postmodern architecture didn’t just change buildings-it changed how we think about what architecture can be.

Where It Ends and What Comes Next

Postmodernism faded as a dominant style by the 1990s, but its DNA is everywhere. Today’s architects don’t call themselves postmodern. But they use its lessons: context matters, history matters, emotion matters.

The next wave-sometimes called neo-eclecticism or critical regionalism-isn’t about parody. It’s about sincerity. It’s about using local materials, responding to climate, honoring cultural identity. But it still asks the same question postmodernism did: Why should a building be boring?

Postmodern architecture didn’t solve all the world’s problems. But it reminded us that buildings aren’t just shelters. They’re expressions. They’re culture made concrete.

What’s the difference between modern and postmodern architecture?

Modern architecture, from the 1920s to 1970s, focused on simplicity, function, and clean lines-think glass towers with no decoration. Postmodern architecture, starting in the 1970s, rejected that. It brought back color, ornament, historical references, and humor. Where modernism said "less is more," postmodernism said "more is more."

Is postmodern architecture still being built today?

Pure postmodernism isn’t common anymore, but its influence is everywhere. Today’s architects mix styles, use bold colors, and reference history-not to mock, but to create meaning. You’ll see it in boutique hotels, cultural centers, and even apartment buildings that blend old and new materials.

Why do some people dislike postmodern buildings?

Some see it as superficial-just adding decorations without real thought. Others think it’s too playful or kitschy. Critics argue it ignores real issues like sustainability and affordability. But supporters say it brought back humanity and cultural identity to architecture, which modernism had stripped away.

Can postmodern architecture be sustainable?

Original postmodern buildings weren’t designed with sustainability in mind-they used lots of glass, steel, and decorative elements that weren’t energy efficient. But today, retrofitted postmodern buildings are being upgraded with insulation, solar panels, and green roofs. The style itself isn’t anti-sustainable-it’s the materials and methods that need updating.

Who were the key architects of postmodernism?

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were the movement’s theorists. Michael Graves designed the iconic Portland Building. Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building became its symbol. Charles Moore created the playful Piazza d’Italia. These four shaped the movement’s visual language and philosophy.

If you walk past a building and feel confused, amused, or oddly moved-it might be postmodern. And that’s exactly how it was meant to be.