How Gothic Architecture Revolutionized Design

Oct, 6 2025

Oct, 6 2025

Gothic vs. Romanesque Architecture Comparison

Gothic Architecture

Emerging in 12th century Europe, known for pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses.

Romanesque Architecture

Predecessor style featuring rounded arches, thick walls, and barrel vaults.

| Feature | Romanesque | Gothic |

|---|---|---|

| Arch Shape | Rounded | Pointed |

| Vault Type | Barrel or groin vault | Ribbed vault |

| Wall Thickness | Massive, load-bearing | Thin, perforated by windows |

| Support System | Embedded buttresses | Flying buttress (external) |

| Light Penetration | Small, high windows | Large stained-glass panels |

Gothic Innovations

- Pointed arches reduce lateral thrust

- Ribbed vaults enable lighter construction

- Flying buttresses allow tall, thin walls

- Stained glass as architectural material

Modern Applications

- Steel-frame skyscrapers

- Lattice façades

- Dynamic glazing systems

- Light-filled office designs

When you walk into a cathedral with soaring vaults and kaleidoscopic light, you’re not just looking at a building - you’re witnessing a design breakthrough that still whispers in today’s studios. Gothic architecture didn’t just change how stone was piled; it rewired the way designers think about structure, light, and emotion. This article unpacks the key inventions, the visual language they created, and why modern architects still copy the medieval playbook.

Defining the style: What makes Gothic architecture distinct?

Gothic architecture is a medieval European building style that emerged in the 12th century and spread across cathedrals, churches, and civic structures. It is characterized by vertical emphasis, expansive stained‑glass windows, and a skeletal structural system that appears to defy gravity. The style grew out of the Romanesque tradition but rejected its heavy, rounded forms in favor of lightness and height.

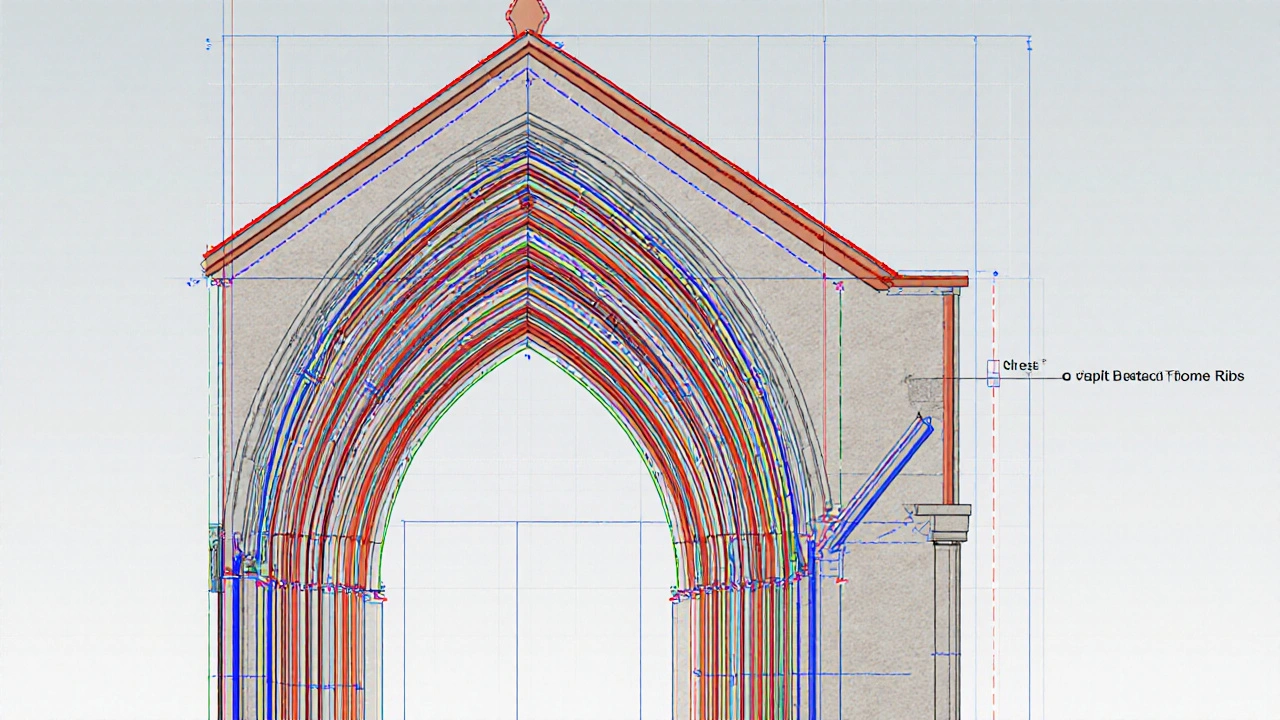

Key visual markers-pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses-work together to create a sense of upward movement. The style also embraced symbolism: light represented divinity, while vertical lines suggested the soul’s ascent.

Structural innovations that shattered the old limits

Flying buttress is a external support system that transfers lateral forces from the high walls to a detached pier. By moving the structural burden outward, walls could be pierced with massive windows without collapsing.

The pointed arch directs weight downwards along two intersecting lines, reducing lateral thrust allowed architects to span wider spaces and build taller openings. Compared with the round Romanesque arch, the pointed form cuts stress more efficiently, enabling the dramatic elevation of nave walls.

Underpinning the ceiling, the ribbed vault uses a framework of intersecting stone ribs to support the ceiling surface. The ribs act like a skeletal backbone, allowing lighter infill panels and faster construction.

These three elements form a structural triangle: flying buttress supports the walls, pointed arches distribute weight, and ribbed vaults carry the roof. The resulting system is both strong and flexible, a principle that modern engineers still reference when designing long‑span bridges and skyscrapers.

Light as material: The stained‑glass revolution

The removal of solid stone walls opened space for stained glass colored glass panels that filter sunlight into narrative scenes. Rather than a decorative afterthought, glass became a structural element that shaped interior experience.

Grand rose windows, like the one at Notre‑Dame Cathedral a 12th‑century Parisian masterpiece famed for its intricate façade and luminous vaults, turned chapels into kaleidoscopes of color. The interplay of light and stone taught designers that ambience could be engineered, a lesson echoed in contemporary “light‑filled” office towers.

From a technical standpoint, the lead cames that hold the glass together form a skeletal network similar to the ribbed vault above. This parallel reinforces the Gothic belief that every component, from stone to metal, can be both decorative and load‑bearing.

From medieval cathedrals to modern design movements

Gothic principles resurfaced dramatically in the 19th‑century Neo‑Gothic revival style that reinterpreted medieval forms for civic and residential buildings. Architects like Augustus Pugin argued that the moral clarity of Gothic ornament could raise societal standards, a view that colored Victorian public works from museums to university halls.

Beyond historic pastiche, the underlying structural ideas migrated into the steel‑frame skyscraper. The early 20th‑century Chicago School used a skeletal framework-much like ribbed vaults-to push façades outward, creating the “Chicago window” that mirrors the Gothic emphasis on light.

Even today’s parametric designers echo the Gothic obsession with verticality and light diffusion. Tools that generate lattice façades draw directly from the geometric logic of flying buttresses, proving that the medieval playbook is still a source of innovation.

What contemporary designers can steal from the Gothic playbook

- Embrace skeletal structures. By letting the support system become a visual feature, you create both efficiency and drama.

- Let light be a material. Use glass, perforated panels, or diffused LEDs to sculpt space, just as stained glass sculpted medieval interiors.

- Vertical emphasis for emotional impact. Tall, slender elements can make a building feel aspirational, a tactic useful in corporate headquarters and cultural venues.

- Integrate symbolism. Align form with narrative-whether it’s a brand story or community value-to give design deeper resonance.

Quick checklist: Applying Gothic concepts today

- Identify load‑bearing walls that could be replaced by external supports (modern buttresses = brise‑soleil, shear walls).

- Choose a pointed‑arch profile for openings to reduce lateral forces.

- Design a rib‑like grid for ceilings or façades; consider exposed steel or timber ribs.

- Select high‑performance glazing that can act as a visual and thermal barrier.

- Map narrative or brand elements onto stained‑glass‑style panels, backlit screens, or perforated metal.

Comparison of key Gothic elements versus Romanesque predecessors

| Feature | Romanesque | Gothic |

|---|---|---|

| Arch shape | Rounded | Pointed |

| Vault type | Barrel or groin vault | Ribbed vault |

| Wall thickness | Massive, load‑bearing | Thin, perforated by windows |

| Support system | Embedded buttresses | Flying buttress (external) |

| Light penetration | Small, high windows | Large stained‑glass panels |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Gothic architects switch to the pointed arch?

The pointed arch channels weight straight down, reducing horizontal thrust. This means walls can be taller and windows larger, which was impossible with the round Romanesque arch.

How did flying buttresses change interior space?

By taking the lateral forces out of the wall, designers could replace stone masses with glass. The result is interiors flooded with colored light, creating a spiritual atmosphere.

Can Gothic structural ideas be used in modern skyscrapers?

Absolutely. The concept of a skeletal frame that bears loads externally is the backbone of steel‑frame towers. Modern engineers also use buttress‑like shear walls to resist wind, echoing the medieval solution.

What is the difference between Neo‑Gothic and original Gothic?

Neo‑Gothic reproduces the visual vocabulary-pointed arches, tracery, and vertical lines-but often uses modern materials like steel and concrete. It’s a stylistic homage rather than a structural necessity.

How did stained glass influence modern lighting design?

Stained glass taught designers that light can be shaped, colored, and diffused intentionally. Today’s architects use fritted glass, LED panels, and dynamic glazing to achieve similar atmospheric effects.